I love breaking news about history. With new technologies like sonar, DNA testing, drones, radar, and chemical analysis, we are resolving historical mysteries faster than ever before.

But sometimes we still find answers through old-fashioned research like poring over primary sources. This is one of those research stories, about Australia during the age of convict ships and Japan during their age of isolation.

In August 1829 the ship Cyprus set sail from a port in Tasmania, heading to the a penal station also in Tasmania. The ship was carrying supplies and 62 people, 31 of whom were convicts. This was a routine trip. Easy.

Until the point when there was no wind to power the sails. The convicts were allowed on deck at that point, attacked the guards, and took control of the ship. Nineteen of the convicts sailed off, leaving the others marooned.

William Swallow was the only mutineer with sailing experience, which will be important later. They sailed around to several islands, with some choosing to stay at those islands. Eventually, Swallow and those still on the ship ended up in Canton, in southern China. They scuttled the Cyprus and pretended to be castaways from another ship.

Swallow and several others were able work for passage back to England, but one of those left behind in Canton confessed and the mutineers were arrested when they reached home. They were tried in London and two of the men were hanged in London for piracy.

During his trial, Swallow swore that he was forced to go along with the others because he was the only one with sailing experience. That saved him from the rope, but he was still returned to prison in Tasmania, where he died four years later.

Now for the samurai. While back in prison, Swallow wrote about his adventure, and mentioned visiting Japan. At that time, January of 1830, Japan had isolated itself from other countries, especially the barbarian westerners. All sailors knew this. So nobody believed Swallow.

Until 2017. That’s when a British-born English teacher and history buff who had lived in Japan for years, Nick Russell, used some amazing primary sources.

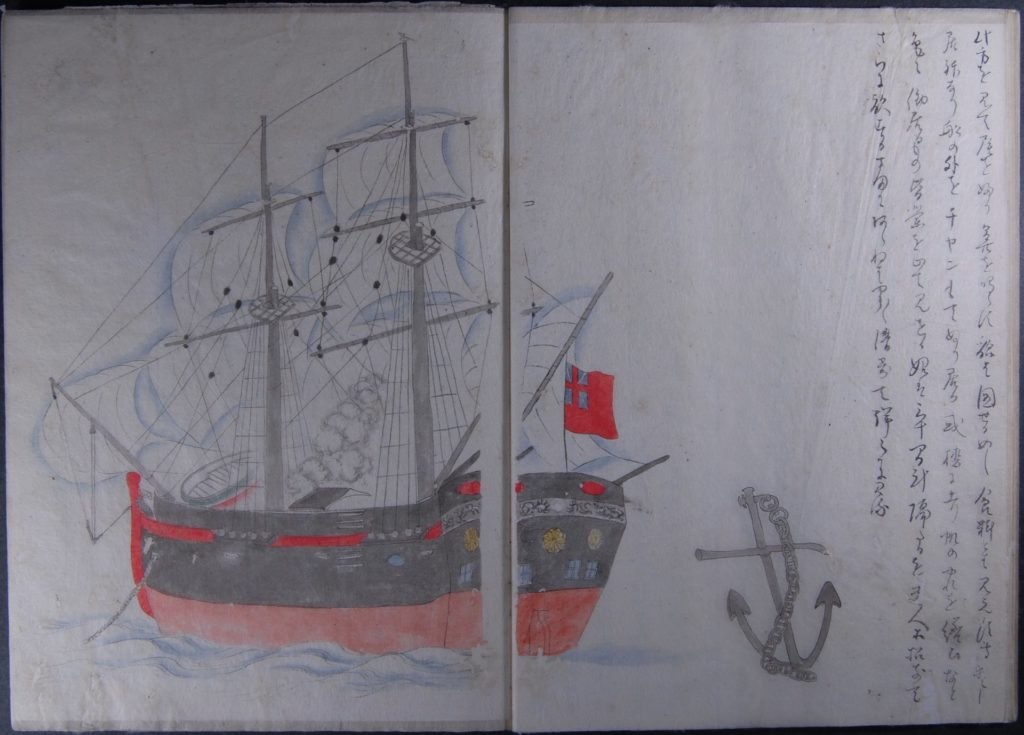

While Japan was rebuffing all outsiders, they had soldiers, samurai, keeping watch along the coasts with orders not to let anyone in. They were also told to keep records of what they saw and what they did to keep Japan safe. Russell and some volunteers translated those old records and discovered mentions and watercolors of a “barbarian” ship documented by two separate samurai at the time that Swallow said he was there requesting water and supplies.

Australian and Japanese officials agree that the story backed up by this research rings true. So you have a mutiny story from Australia that was pretty famous in Australia. Then you have the Japanese story of the barbarian ship driven away by the samurai that is pretty famous in Japan. And it all, finally, fits nicely together.

Some of you are probably wondering why this sort of thing matters and why I love when history has breaking news. Although it is fun and interesting, does it matter that Swallow wasn’t lying? Or that the samurai didn’t kill the sailors while they had the chance?

Truth matters. We know more than we knew before. Maybe this connection will lead to other connections. Facts matter.

I would love to hear from my readers. What historical mystery would you most like to see resolved? What one bit of truth would you like to know for sure?

Oak Island Treasure. Did someone already find it? Are they looking for nothing? Why, if it’s really there, is it there?

I did a quick search and didn’t realize this was such a thing. They even have a TV show?! With something this high profile, you can bet it’ll be all over social media if they ever find a treasure. Especially since there is such a variety of theories.

Thanks for asking!

Cathy