I’ve been thinking lately about protests, for obvious reasons. There are many types of protests and demonstrations. The concept is not specific to any culture or desired result, but exists globally. It’s also not specific to a particular era and you can find examples throughout history.

During the time when the sun never set on the British Empire, India was under British rule from 1858 until 1947. But India wanted self-rule and they found a leader for this nationalist movement in Mohandas Gandhi (1869-1948).

Gandhi and other Indians took a strategic and long-term route to breaking from the British. This wasn’t about one demonstration or protest, but there is just one that I want to share.

The British controlled, among other things, the production and distribution of salt. It was illegal for the Indian population to produce or manufacture their own salt. They were required to purchase more expensive and heavily taxed salt from the British government. This salt tax affected Indians of all classes, but was especially a burden on the poor.

Because the salt tax affected everyone, it was the perfect protest to gather support among Indians. In 1930, Gandhi began a march to the Indian Ocean to commit an act of non-violent civil disobedience. In less than a month, he and his followers walked about 240 miles. Each night when they stopped, they drew crowds and spoke about what they were doing, and why it was important.

Gandhi at Dandi, South Gujarat, picking salt on the beach at the end of the Salt March, 5 April 1930. Behind him is his second son Manilal Gandhi and Mithuben Petit. Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Finally they reached the coast and picked up some salt, which was an illegal act. Although no one was arrested that day, the illegal acts continued. Eventually, Gandhi and others were arrested, but that wasn’t enough to stop this protest. In time, as the protests continued, about 60,000 Indians were arrested and jailed for illegally producing salt.

As you can imagine, taking care of 60,000 new prisoners was a bit of a hassle for the British jailers. It also didn’t help the British that the march and subsequent acts of civil disobedience drew international press attention. It was clear that, just as the Boston Tea Party was not about tea, this was not just about salt.

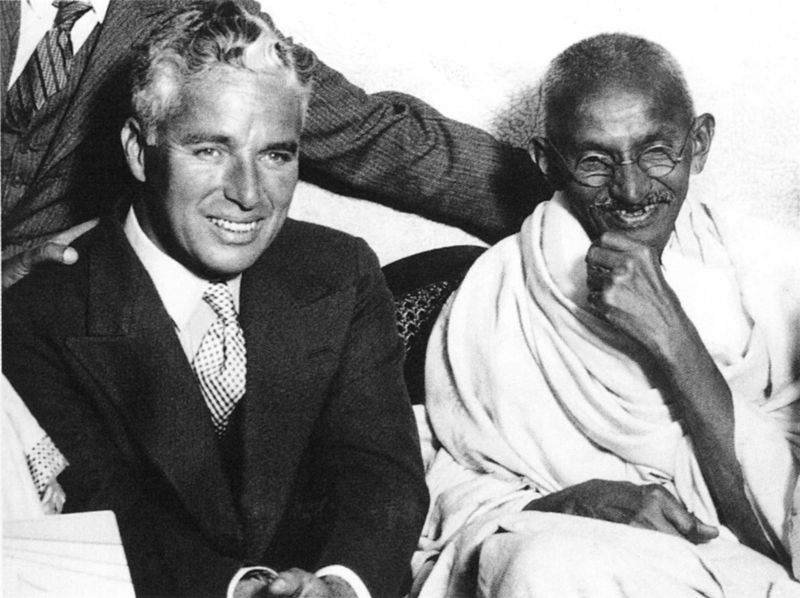

Gandhi meets with Charlie Chaplin at the home of Dr. Kaitial in Canning Town, London, September 22, 1931. Photo via Wikimedia Commons

The thing about protests is that there are two sides and the actions of both sides are often illuminating about deeper issues. Both the protesters and those being protested against want something, and how they each act determines the results of the protest.

In this case, the result was the 1931 Gandhi-Irwin Pact. Gandhi and Lord Irwin, the Viceroy of India, agreed that Gandhi would stop his salt protests and the British authorities would release all who had been imprisoned for salt offenses and would also allow Indians to produce their own salt for domestic use.

Depending upon your personality, you could call this either a win-win or lose-lose situation. The British lost some tax revenue and the protesters didn’t get their ultimate goal of self-rule, at least not that day. That didn’t happen for another sixteen years. But this protest, the sense of unity shared by the Indian people working toward a common goal, was one of the building blocks that led to that final result.