There is a lot of stuff in the history of medicine that can make modern audiences cringe and wonder what the heck those people were thinking. Of course, it’s entirely possible that in 100 years, 500 years or 3,000 years, future historians will study our current medical practices and have the same reaction.

Strangely enough, one medical constant throughout history has been bloodletting. For the past 3,000 years, in all areas of the world, with a variety of medical justifications, people have been bled for health. Physicians bled people not only when they were ill, but also as a preventative measure to keep them from becoming ill. The medical reasons and the methods changed, but the treatment remained the same.

A surgeon letting blood from a woman’s arm, and a physician examining a urine-flask. Oil painting by a Flemish painter, 18th (?) century. This file comes from Wellcome Images, a website operated by Wellcome Trust, a global charitable foundation based in the United Kingdom.

I always picture the bloodletting being done by leeches, but that was actually a small part of the whole. Leeches produce anti-coagulants and anesthetics, so it is less painful for the patients than other methods. The need for leeches, especially in the 19th century, led to a profession, left mostly to women, as leech collectors. I’ll try to remember that option the next time I complain about my job.

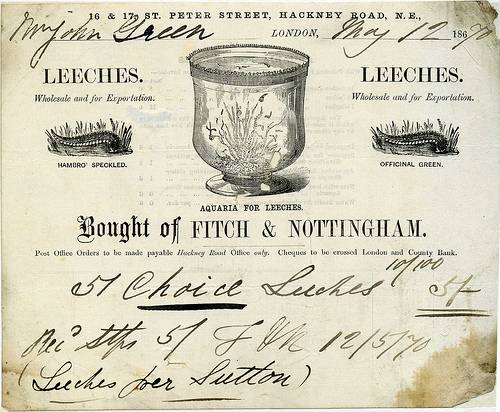

1870 receipt for the purchase of medical leeches from Fitch & Nottingham, London. From Swindon Local Studies Collection.

Instead of leeches, most bloodletting was done with sharp objects, such as lancets (double-edged knives) and, my personal favorite, the scarificator. Yes, it’s hard not to notice the word “scar” is right there in the name of the device, and the pronunciation sounds like “scare”. Scarificators generally had 4-12 sharp blades that were spring-loaded to make superficial cuts in the skin, all in the same area and of a uniform depth. The blood was then collected in a bowl.

Automatic scarifier, by W. H. Hutchison, Sheffield, 19th c. This file comes from Wellcome Images, a website operated by Wellcome Trust, a global charitable foundation based in the United Kingdom.

It wasn’t until the mid-nineteenth century that Ignaz Semmelweis, a Hungarian physician, demonstrated that hand-washing, and the washing of medical tools, could save lives. Knowing this, the first thing I wondered when reading about the scarificator was how many people ended up with new infections or died because the device was not cleaned after each use.

An English scarificator with six lancets used for blood-letting made by Fuller of London. This file comes from Wellcome Images, a website operated by Wellcome Trust, a global charitable foundation based in the United Kingdom.

Bloodletting was finally replaced in most instances by a variety of other treatment and medications at the end of the 19th century. There is no way to tell how many times over the centuries that bloodletting killed a patient rather than saving them. Doctors seemed to apply bloodletting when they didn’t know what else to do, believing that it was better to something than do nothing, often bleeding the patient until they passed out from blood loss. I find it amazing that anyone believed that any one treatment could work for all ailments.

Bloodletting is still used today, although in very specific instances and without the scary tools. But we are still using leeches. Maybe we will still be bleeding patients for another 3,000 years. If not, there is an active collectors’ market for antique medical tools. Just one of the many ways to research history.